The Aviary - A Fantasy about Freedom

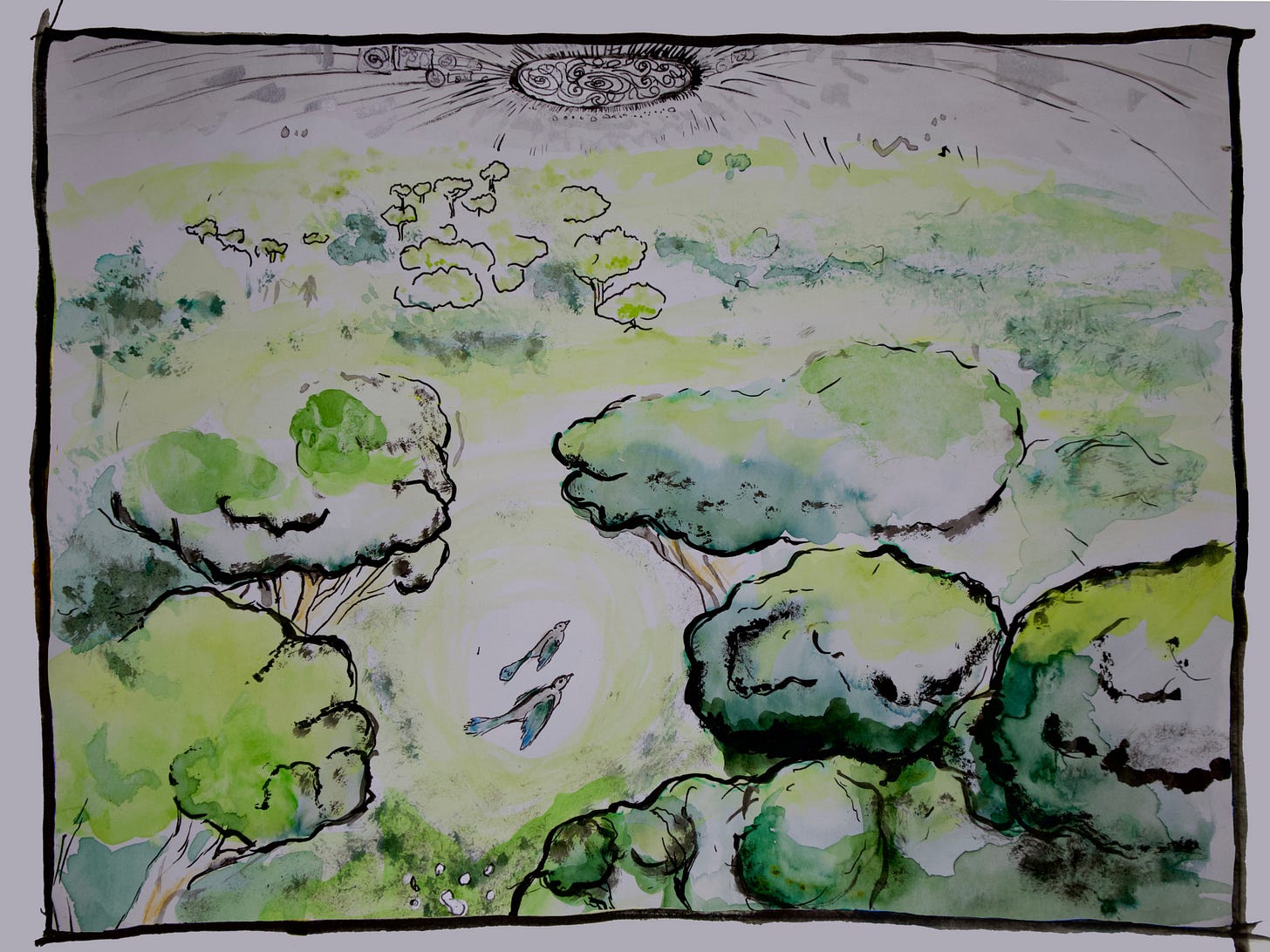

On a distant planet, a group of beautiful birds in an ornate aviary discover a hole to the huge forest outside.

Story by CJ Harrington. Illustrations by Stef D Zaster.

Every morning the beautiful birds wake in their roosts to the caretaker’s distant song calling them to gather for breakfast in the feeding area on the eastern side of the huge, ornate aviary. They arrive in ones and twos, and threes and more. Flitting in like magic. Swooping. Hopping. Strutting. Squishing their soft bodies together under the weaved willow canopy, and wriggling with excitement – hustling, bustling, and jostling each other. Their tiny feet scratch eagerly on the yellow, dusty ground as they quietly chirp, tweet, and coo to one another. Their tails and crests dance gently in the air above them like a technicolour meadow swaying softly to the music of a changing breeze.

The blue-bodied mimic bird quietly watches them arrive, standing under the fossilised light portal plant beside the fresh-water spring in the feeding area, listening carefully to the caretaker’s song.

In the distance, on the far side of the aviary, flakes of silver silently begin to fall to the floor. One by one. Sweeping and spinning. Two by two through the air. Threes, fours, tens, hundreds. More and more and more.

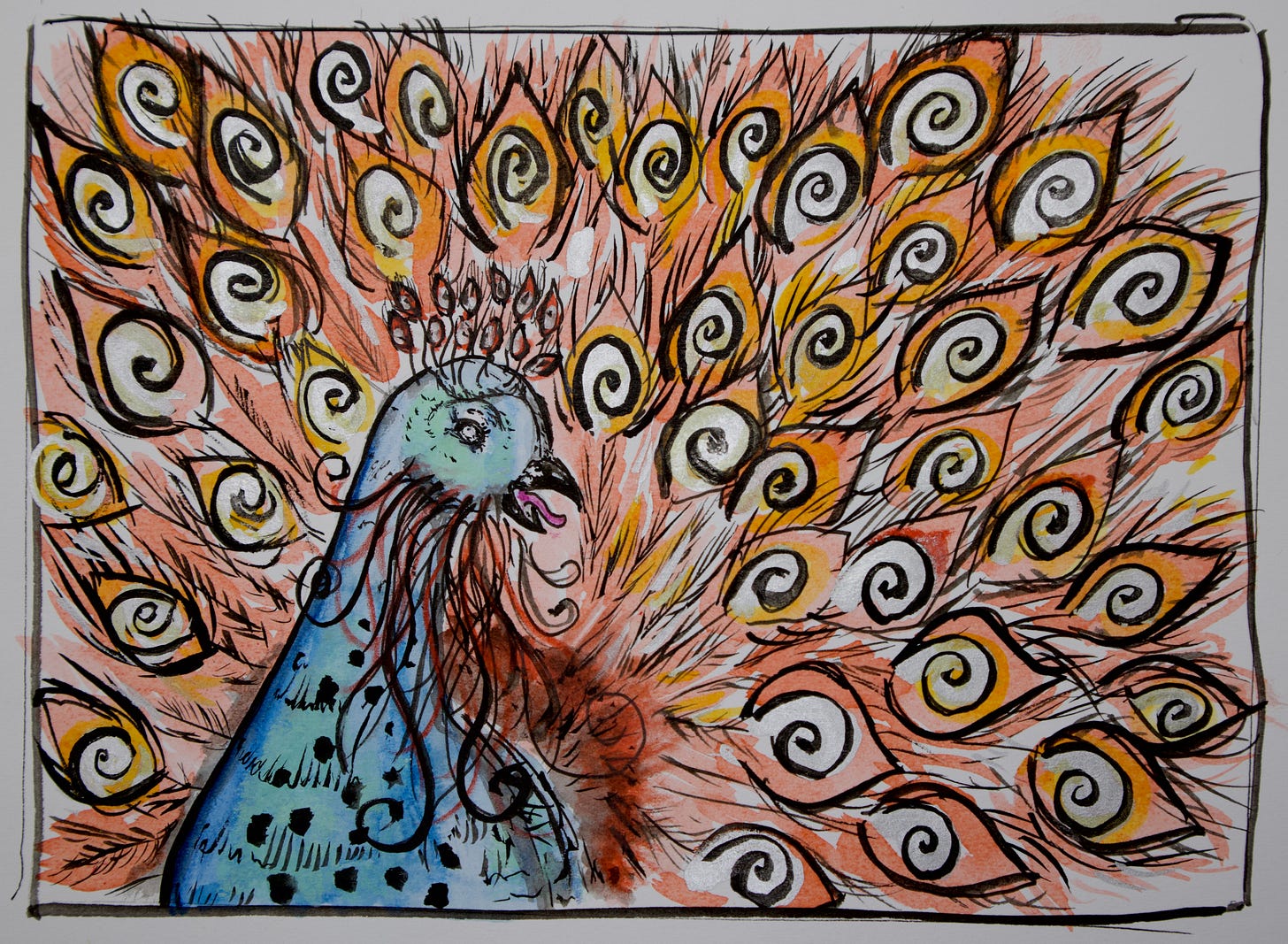

When the mimic bird has understood the caretaker’s song he steps forward, folds behind him his wide clay-red and silver peacock-ish tail, softly bows his long, black-flecked neck, and slowly blinks his tiny white eyes. A motion that is a mark of respect and trust between friends of a feather.

“She is bringing us sky fruits, nut fruits, nut bugs, crunchy bats and gramfy croojers.” The mimic bird’s natural abilities (more advanced than the lyrebird’s, the minor bird’s, the parrot’s, and the least secretive of the corvid’s) mean that he can recognise, understand, translate, and learn to repeat any sounds from his environment.

He is always listening and learning.

Upon hearing the caretaker’s sung menu translated and relayed to them by the mimic bird, the melodies and rhythms of the gathered birds’ growing anticipation climb to a joyous crescendo, and they hop, bop, jump and jive together in the long light of the rising sun. Waiting patiently but excitedly.

There are no doors or openings of any kind on the aviary. Only the caretaker can bring things in and out. It is made of iron panels of varying size and shape, which are intricately hand cut and etched in a fine filigree design, and held together by a strong steel frame. All of which is silver plated.

When the caretaker is not out catching food for the birds, or back at her small home preparing the food, or sitting inside the aviary enjoying the beauty she takes care of, much of the rest of her time is spent maintaining the polish of the frame and panels.

Her tall silhouette soon follows her song out of the dense ancient forest that surrounds the aviary. She has huge wide eyes, long dark hair almost all the way to the ground and walks upright with a bouncing gait. Her arms are noticeably longer than a human’s and her legs have two joints one- and two-thirds up, which bend in opposing directions. Her feet are shorter and wider than ours and her skin is covered in a light and slightly rough fur. She strides purposely, with a huge smile on her face, carrying five small sacks of food over her left shoulder.

When she comes close to the frame of the aviary her pace does not slow. She casually puts her free hand in her pocket and an oval rainbow-coloured light flashes once around her and she disappears. Then the rainbow light flashes again as she re-materialises inside the aviary, along with her sacks of food, having not missed a step or a breath.

With his tail still tucked up neatly behind him, the mimic bird lowers his head to the ground and moves quickly but carefully towards the caretaker – his right eye turned up and his long eyelashes gently fluttering.

“Hello, my darling,” says the caretaker, making eye contact as she comes to a stop.

She crouches to gently place her bags of food on the ground beside her, standing each one upright on the floor by her feet, and then she blinks slowly and intentionally as she reaches out.

The mimic bird raises his head to meet her hand, shuffles his tail excitedly, and moves in close to her body for a hug. He clicks and chirrups softly while she strokes, squeezes and ruffles the feathers and muscles on his cheek and crown for a few soft seconds before he steps back and speaks.

“All, all, all.” He knows what the noises will mean to her.

The caretaker jumps, laughs a little and then smiles at his enthusiasm.

“I knew everyone would like the choices today. I’m glad I won’t have to take any food back,” she smiles.

The mimic bird sweeps round to stand along side her. He picks while she unsticks, and together they unfold and roll down the ends of each bag of food. The excited patience of the happy, hungry crowd of birds relaxes as they smell their favourite foods.

The red cotton-tailed birds come forward first, with their downy-soft puffball tails bobbing along behind them. They sing their food choices to the mimic bird, their song bouncing through the air on notes that sound round and gentle, like bubbles dancing on a xylophone.

The mimic bird listens carefully, his eyes closed and his head nodding a little – clearly enjoying the melody as well as understanding and interpreting – before he translates their songs to the caretaker.

The caretaker swiftly stoops and scoops large handfuls of nut fruits, nut bugs, and gramfy croojers from three of the bags. Then she stretches as far to her left as she can and makes tidy piles of the food on the floor for the red cotton-tailed birds to enjoy.

The northern finotias step forward next, then the twist-billed birds of wonder, the seven stringed harpists, and the triple muse birds.

Each time the mimic bird translates their requests for the caretaker. And each time, she listens attentively and makes little piles of what the birds each want from her bags.

The 13 species of bird that live in the aviary with the mimic bird all patiently come forward group by group – the last in line still fidgeting and twittering with excited patience while they wait their turn.

Then the mimic bird asks for what he would like to eat.

Once they’re all feeding happily the caretaker takes a walk around the feeding area, stopping for a short time with each group to stroke and cuddle them before she says goodbye to the mimic bird and leaves them all to finish their food, disappearing quietly with another brisk stride and rainbow flash back into the dense woodland outside.

The birds finish their morning feast, eagerly scratching and pecking at the yellow dusty ground to find and scoff every morsel and mouthful. The twist billed birds of wonder even able to drill into cracks in the ground where their sky fruits have fallen.

When they are sure they have eaten every bit, they leave the feeding area together to return slowly with heavy little bellies to the small, green woodland in the centre of the aviary.

Some of them are so weighed down with their satisfaction that they even walk rather than fly!

But the tiny northern finotias are always ahead, zipping through the air with rapid wing beats that sound like fairy-sized motorbikes. Nothing weighs them down. Usually, they are first to reach the top tips of the tallest trees that have the broadest view of the whole aviary and look out furthest into the outside forest, too.

But today the finotias find that bright sparks of light from the ground flash in their eyes as they approach, disorientating their flight. They circle the wood but find they cannot make a safe landing, so they fly swiftly back to the slower crowd of birds.

“We can’t see the trees properly,” some of them twitter.

“Bright rain has fallen,” some others tweet.

“Still water has shattered,” the more imaginative ones chitter.

“Come and see, come and see,” they all sing in unison, before zooming off again back towards the now sparkling wood.

Despite their heavy little bellies, the rest of the birds find that the finotias’ enigmatic excitement encourages or enables them to pick up pace and follow.

When they all arrive together, they see that a wide circle of glittery silver flakes covers the trees and bushes on the edge of the small woodland, and on a large patch of the grassy heathland floor that surrounds the woodland.

A few of the golden tchickets wobblingly hop their fat little bodies forward to investigate, or perhaps to compare the sparkle of these mysterious silver flakes with the bright gold glitter in their wings.

The mimic bird pecks inquisitively at some of the flakes on the floor at his feet. They disintegrate easily, eventually into dust. He carefully picks up one with his beak and moves it through the air – seeing how it glints in the light and flexes with the motion.

Many of the other birds, most in fact, are more tentative with their response. Some even showing signs of uncertainty and fear; keeping their distance, backing away, trying not to get any flakes on them – just in case.

“The aviary is moulting,” says the mimic bird as the flake of silver falls from his beak.

Two of the Twynop’s flat wings (which, at more than four times the size of the little finotias, are the largest of the birds in the aviary except the mimic bird) immediately spread their wide wings and run to take off.

They climb slowly at first, circling for a while before swooping low over the heads of the group, gathering speed and climbing again.

Once above the tree line they quickly find a thermal and rise in a shot to the distant roof of the aviary.

Reaching the top of the aviary quickly on the thermal, the two flat-wing birds find that the centre circular panel at the very peak of the aviary’s dome is still in place. As are all the panels around it. And, aside from a few chips and scratches, there is no sign of the silver-plating there having flaked off the frame in the quantities it has landed far below.

They spiral swiftly and silently together around the single, sweeping wall of the aviary. Checking it thoroughly from top to bottom. Widening and widening their circle as they go.

About a quarter of the way down, they discover a hole where one of the steel, silver-plated, filigree panels should be – on the side of the aviary closest to the edge of the woodland.

The frame that is left behind is twisted. Small sections of the panel remain – torn, bent, hanging off. Sharp, frayed bits of metal poke and rip along the jagged edges of the hole.

Rust from the iron bolts and rivets, which hold together the frame and panels, must’ve been bubbling up underneath the shine for years.

Decades, likely…

Centuries, probably…

One of the flat-wings hovers close to the hole left by the fallen panel. The hole is easily big enough for the bird to fit through.

But no bird has ever left the aviary.

Some birds have been brought in from outside by the caretaker to be healed, and these have all stayed.

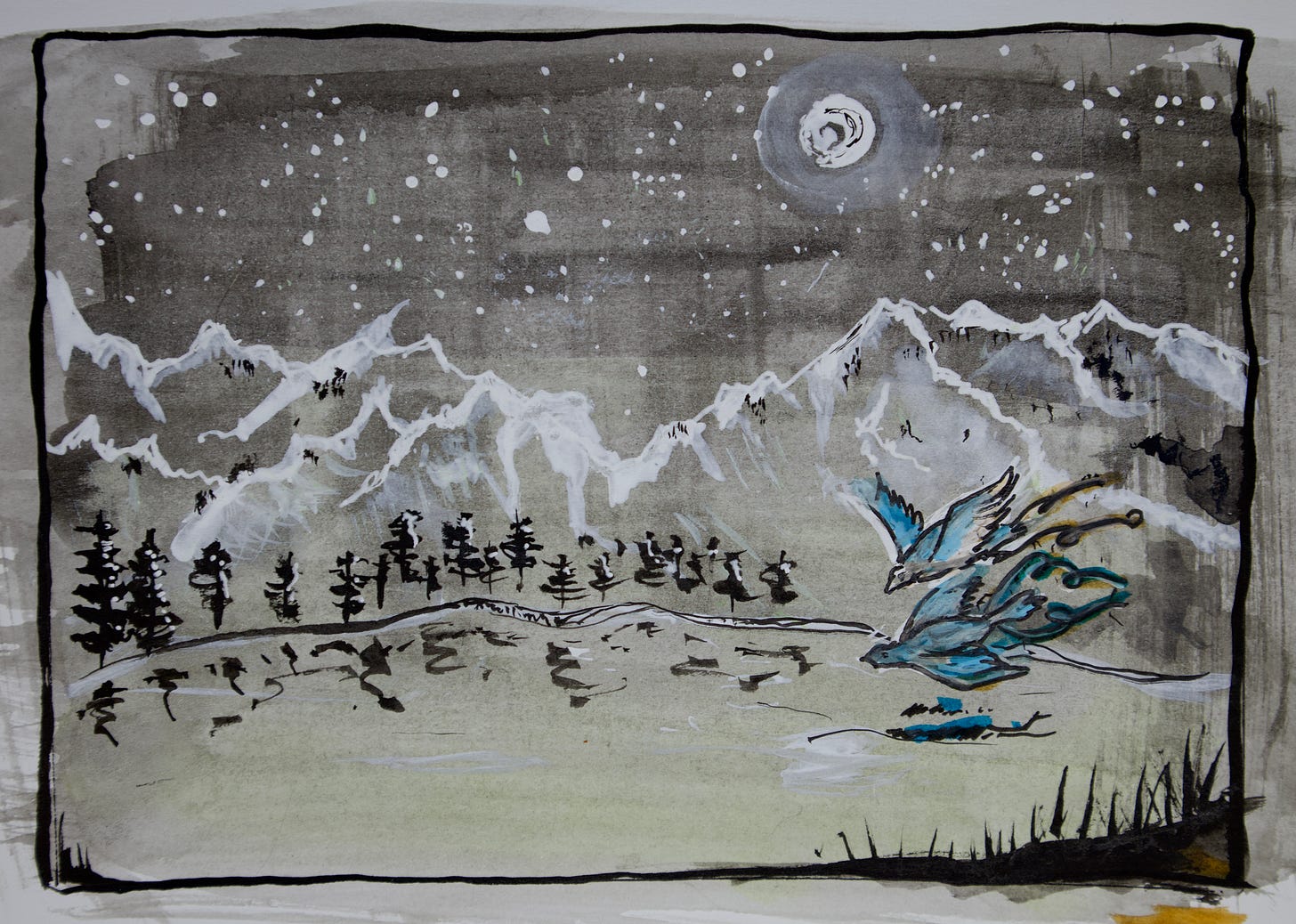

Over the years, these outside birds have told many stories about their past lives in the forest. Adding confirmation and tantalising detail to the strange noises and flashes of motion, colour and form that the inside birds have always thought they might be hearing and seeing through the small gaps in the frame.

Sometimes an outside bird have told them all about other kinds of beings that live in the forest, but sometimes the same outside bird will deny the existence of these other beings. It is never clear from this behaviour whether it is just cheeky antics or something else.

Maybe the outside birds feel the need to protect the inside birds from knowing too much. Maybe the outside birds are beginning to forget – or choosing to.

Even so, as more outside stories are told, more and more of the inside birds begin to wonder what it might be like to explore or even live in the deep dark forest outside.

But no bird has ever left the aviary.

The other flat-wing slips by its hovering companion and perches gingerly on the edge of the hole, looking out into the forest and down the outside of the dome. There are scratches and scuffs from the panel’s slide down the curve, all the way to the ground where it now rests.

This is a change that no bird in the aviary was expecting. The option to explore.

The flat-wing sitting on the lip of the hole leans forward slowly, but a strong gust of wind whips up the side of the aviary and tilts her back, blowing her off her perch and inside. She goes with the motion, rolling to the left as she somersaults, and joins her companion hovering in the air.

With a slight tilt of their tails, the flat-wings slip backwards together, wheel round and dive back down to the ground – returning together to all the other birds.

“There’s a hole in the aviary frame,” one of the flat-wings cries to the whole group of birds as it lands.

“We can go out into the huge forest,” the other one says as it shakes out its tail.

“Out, out, out,” they both continue, proudly and excitedly strutting around.

Without asking the flat-wings where the hole is, the tall, slender, inquisitive ottus all immediately crouch. Then, just as quickly, they spring high into the air together with their wings held close to their body and their long legs kept neatly tucked up inside their pantaloon-like feather-skirts around their waist.

At the peak of the trajectory of their leap, their wings open in unison to play a flurry of drum rolls in the air as the ottus take flight.

They quickly find the hole and excitedly push and shove their way outside in seconds, while the rest of the birds are still shuffling and wriggling and chittering and chattering far beneath them.

After all of the ottus left quickly together through the hole in The Aviary to explore the forest outside, a small group of the flat-wings and a few of the bright, parrot-like radiant cottlers quickly and eagerly follow too – leaving behind the rest of their groups.

Then most of the daycurblers, whose feathers are mottled with a cloud-like pattern, and about half of the fancy roloops, their pretty curled tails twisting in the slip stream behind them, also take to the skies and rise.

And it isn’t long before many of the wind riders and the fat, little, golden tchickets have also started to explore.

But some birds stay within The Aviary.

Unsure. Scared. Nervous.

Not interested. More considered.

Still too full to fly!

Waiting…

Eventually, all of the birds who’d wanted to go out but had been feeling too full also leave The Aviary, leaving behind only the group of birds who are unsure of the outside.

Hours pass before the first bird returns in the early afternoon to the now silent and slightly nervous group of birds that stayed behind.

It is one of the radiant cottlers who flies in first; twit-twit-twitting full of excitement.

“I saw a bright blue bird with a long thin beak. It was hovering not flying and it was singing about sweet flower juice,” she sings joyfully.

This news doesn’t feel as exciting to the nervous group of birds who stayed behind as it does to her.

They imagine different kinds of blue bird; bigger/smaller/grumpy/stern…they aren’t sure what to expect.

But a few of the nervous birds can sense that the cottler did have a lovely time outside and this softens their reaction and opens them to her story.

A few minutes after the first radiant cottler came back with news of strange blue birds outside, two fancy roloops also return – the long curls of their tails sweep and spin across the dusty floor as they swoop long and low before landing.

“Being able to go out fills me full of joy and wonder. There is so much to explore,” coos the first, in the distinctive, soft, curly-purring-coo of the roloop.

“We saw giant hills made of rock covered in cold, fluffy water. There is so much to discover. Outside is new, unknown and exciting,“ his companion adds.

Then they immediately swish off together, high into The Aviary, their tails spinning in their wake like bright party streamers all the way to the hole and back into the outside again – briefly marking out a bright rainbow course in the sky.

Some of the birds who’d enjoyed hearing the cottler’s story of the blue bird are also enthused by the roloops’ excitement and soon follow them out, leaving behind only those who’s insecurities about the outside are the strongest.

Not long after the roloop’s brief visit to the unsure crowd, a wind rider swoops down from the aviary roof and over their heads, squawking as he passes.

“I went so high my ears screamed. I saw all of the forest and beyond. Freedom is huge. The aviary is too small now. Hole is good. Freedom is good.”

And he disappears off, up and out again.

For the birds still inside the aviary, the idea of this huge freedom is beginning to feel confusing, something they can’t comprehend, something they never wanted and still don’t – both scary and unnecessary.

Too much enthusiasm is sometimes as bad as resistance and fear, when it comes to responding to change.

One of the radiant cottlers who stayed behind with all the worried birds cuddles its two chicks and opens its beak to sing about the safety and beauty inside The Aviary.

But before the cottler can put notes to its feelings, a round little sparkling tchicket drops into the group from above bouncing hoppily and shedding glitter from its wings as it flutters before them.

“I have been safe in the aviary since my accident. I always remembered the wild but never wanted to speak of it. I remembered it sometimes being cold, sometimes I was scared and hungry, or sometimes I had to eat nasty food. And I always remembered my scary accident. I have been so happy and safe in the aviary since then. I’ve felt protected by the boundaries. But I had forgotten the fun of the wild wind. It still feels the same as I remember in my healed wing. And I had forgotten the sweetness of ripe berries plucked from a branch. And the joy of new visions, new experiences, longer distances. Discovery! And now I remember so many big, huge joys from the outside too. The aviary is safe but now it’s too small for me.”

The tchicket zips off again, leaving a comet-like glittery trail in the air behind it.

And the radiant cottler begins to try to find its song again.

The radiant cottler only gets to sing two soft notes to her chicks under her breath before one of the red cotton-tailed birds who’d been outside lands in front of the worried group of birds, full to puffing-up with an urgent story.

“The creatures of my dreams exist,” she whistles high and bright.

“The furry ones with hands like the caretaker’s but more fingers. They store their food in their cheeks,” she tweets a tinkly little laugh.

“They jump and don’t fly. They dig up the ground. They are real. They are real. They are not just in my dreams.”

The prospect of new and unusual animals outside, and possibly also coming into the aviary if they can climb up to the hole, worries the radiant cottler – but she keeps quiet while All the birds who’ve been exploring outside begin to stream in.

Swooping in groupings, slipping and sweeping through the air creating a fluttering rainbow in the aviary sky.

The cotton-tailed bird is still bobbling about on the ground below as they begin to land. Her round puffy tail bounces up and down and left and right as she twitters on excitedly about how cute the outside animals are.

And the radiant cottler is still trying to find the tune she needs to sing to communicate her worries about freedom and outside.

The last group of birds to return are the pretty pink ottus, letting their delicate legs dangle out of their feathered petticoats as they bring the bird rainbow to the ground.

“We’ve been racing outside birds.”

“The caretaker is outside the aviary.”

“There are some amazing aerobatic fliers out there.”

“The wind above the trees is so strong and fun to fly in.”

“The caretaker is coming to fix the hole.”

“The outside birds are fun to play with.”

“The caretaker has a big box of tools to fix the hole.”

“The caretaker is climbing up the outside right now.”

Upon hearing that the caretaker is on her way to mend the hole, the crowd of birds – the explorers and the wary together again now after everybird returned from outside – all fall silent briefly; the rustley shuffle of feathers and dusty scritch of claws in the dirt ticking up the empty tension of the moment.

A small group of roloops break the silence first, whispering together on the edge of the group about how safe their childhood was inside the aviary and how they want the same securities for their fledglings. They are glad the hole is being closed.

In the centre of the group, the nervous radiant cottler finds her song but is not brave enough to sing for the whole crowd, so she begins twittering gently just to a few finotias who are nearby.

“Wild birds might lay their eggs in our nests or bring seeds of new strange plants into the aviary…” she has much to express.

Her song worries the poor little finotias…they begin to see why it might be a good idea to close the hole, too.

One of the twist-billed birds of wonder speaks up above the chitter of the crowd.

“I loved being out. No longer want to stay in all the time. Now that I’ve been out, I know I need to go out sometimes. I love the freedoms we have in the aviary, but I have realised that freedom is more than what we have in here. The hole must stay open.”

Some of the birds agree with him; moving to stand nearer to him, putting their voices behind him, and repeating and echoing the word “freedom”.

The radiant cottler steps forward, finally finding the strength in her voice to express herself and stand opposed to the twist-bill and the growing chorus who want the hole to stay open .

“The hole is too dangerous. It must be fixed. We need to keep the security of The Aviary.”

Many birds move to stand closer to the cottler, also in agreement with her. Picking up on her word “security”.

And some birds quietly move to shelter silently under the nearby silver-flaked bushes; side stepping the initial divisions, and watching and listening as the opinions begin to turn into a fraught and complex discussion.

Soon, most of the birds have settled their hearts and minds on one side or the other of the discussion – talking together in small groups about their hopes or worries, or joining one of the two larger groups that have formed in the centre of the aviary on the edge of the small wood.

Only the mimic bird does not join in. He remains quiet and walks slowly through the crowd listening to them all; paying attention and doing his best to understand each of the views he hears.

A group of fancy roloops are nervously wondering if outside animals will come into the aviary and attack them.

Three of the seven-stringed harpists want to be allowed to go out still, because they were planning on singing their best songs from the tops of the tallest trees to see if they can meet any other animals that are as melodically masterful as they are.

One flat-wing is doing its best to persuade all the other flat-wings that the outside birds will be just as friendly as everyone inside the aviary.

Even the gentle, loving tchickets, finotias and cotton-tails find reasons to oppose one another.

All the while, the mimic bird continues walking through the crowd – taking his time.

The conversation flows around the group, with the birds changing their minds and shifting their opinions as they hear of new possible fears and potential joys from others around them.

The mimic bird sits quietly, listening still.

He hears birds disagreeing about their reasons for wanting and needing this increased freedom, rather than acknowledging together that they have one common need – freedom.

And he hears the same from the groups of birds who want the hole to remain closed. Individual/personal definitions of safety being discussed and argued over. Without realising they are all talking about the same thing.

This kind of disagreement has never happened in The Aviary. The birds have always had a safe and protected life inside. And they’d always felt free inside, too. Free to make any choice they liked within the frame of the aviary which kept them safe. In fact, most of them never really considered that freedom could have different definitions, varied sizes, different scopes for different birds. Most of them just accepted that the freedom they had within The Aviary was The Definition of Freedom for Every Bird.

But since the hole, the knowledge of what freedom is and what it might mean has changed for many of birds. As has the sense of safety and security.

Before the division between the birds becomes discord, the mimic bird makes a huge heavy feathery fuss out of hopping high up in a tree.

Squawking loudly, whipping up huge gusts of wind, and sending eddies of dust, leaves and gravel all around as he does.

The weight of his plumage makes it impossible to take off from the ground.

By the time he has clambered all the way to the top of the tree, the birds below have all taken notice of his kerfuffle and settled into silence – looking up at him as he suddenly dives towards the group.

He falls fast.

With his wings closed and tail tucked in tight, he plummets like a rucksack full of clothes!

Then he spreads his wings and tail, wobbles for a moment as he gains control, and swoops low over the heads of all the birds below.

The taller birds feel his belly feathers on their plumes and the eyes of the whole group follow him as he arcs round to land on a large tree stump behind them.

Standing tall upon the tree stump, the mimic bird raises his eyes to the skies, takes a long slow breath, then with a soft blink and slow bow he lowers his gaze to the crowd of birds below.

“Some of us want to keep this new freedom. Some want to keep the aviary as safe as always. I have heard so many good reasons for both. And we must not make this a choice.”

The crowd begin to murmur but he carries on.

“It cannot be one or the other.”

The murmur continues, flowing and growing in ripples and waves around the group.

“Birds who want the freedom of the hole, do you want to leave the safety of the aviary forever?”

Parts of the murmur squawk, caw, screech and whistle back strongly.

“No.”

“And birds who want safety, do you want to stop others exploring and never be able to explore yourself?”

Another part of the murmur replies.

“No.”

The mimic bird pauses.

The murmur of the birds settles to a gentle background bubble of tweets and twoots as the mimic bird forms the words he needs to continue.

“We all need freedom. We all need safety. We all need both. We are all the same.”

Having only been disagreeing for a few minutes, it is quite easy for the birds to all see their similarities, set aside their personal differences, and return together to their core mutual needs.

It would have been much harder for them to come together so quickly if their differences were deeply entrenched and reinforced through generations and expectations (and much more necessary too, many would argue).

The crowd is quick to pick up the rhythm of his words.

“All need freedom. All need safety. All need both. All the same.”

Their coos, twees, chitters, chatters, squawks and clickerits get stronger and stronger as their songs grow in unison together.

“All need freedom. All need safety. All need both. All the same.”

The song fills some of the birds’ little bodies with confidence and joy as they fully understand that they are all the same and they all have the same needs.

They stand tall, looking around at all the other birds coming together, realising clearly what their needs are together.

Caught in the swift sweep of simplicity and clarity, they take off, circling the group, chanting in the air.

“All need freedom. All need safety. All need both. All the same.”

Quickly, in bright clouds of tens and twenties, the other birds all join them – filling the sky inside the aviary.

“All need freedom. All need safety. All need both. All the same.”

The murmuration rises to the roof of the aviary, circling and singing, circling and singing, circling and singing.

“All need freedom. All need safety. All need both. All the same.”

“All need freedom. All need safety. All need both. All the same.”

“All need freedom. All need safety. All need both. All the same.”

At the glorious sight and sound of all the birds’ passion for their safety and their freedom, the mimic bird decides to take his first trip outside.

He hops and flaps high up in the branches of a nearby tree again, then swoops down toward the ground to gather speed before pulling up and rolling over to fly.

The huge beats of his wings leap him through great gaps in the air and the treetops seem to bow with respect as he climbs past fast.

Gripping the top edge of the hole with his huge claws, he hangs upside down to lean, twist and arch his body clumsily through, then pays slow and careful attention to pulling his tail through too, so as not to shred his feathers on the jagged edges.

Once safely perched sideways on the outside of the aviary, he is immediately distracted from any thought of exploration by discovering that the caretaker has already climbed all the way up and attached a wooden working platform to the aviary about three feet under the hole.

Beside her on the platform, along with the broken panel she brought back up with her from the ground below, she has her toolbox, a small sack full of nuts, bolts and rivets, and a roll of silver.

The mimic drops down to join her.

“Hello my dear.” The caretaker is only briefly surprised to see the mimic bird land on the platform beside her.

She reaches down to greet him with a gentle stroke on his head, then stands again to look closely at the hole.

“You should go back inside, I am going to fix this now.”

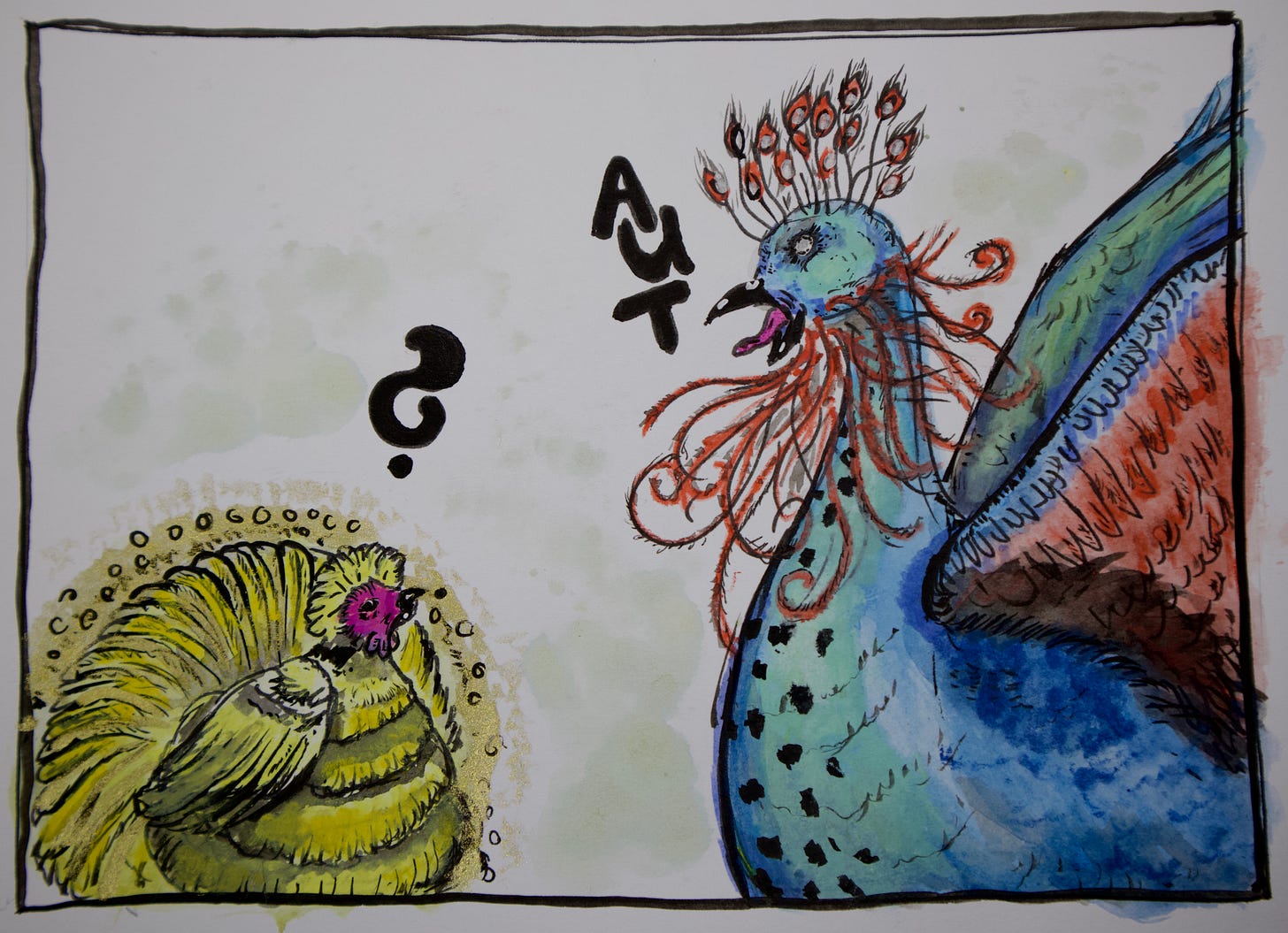

The mimic bird knows how to make the caretaker’s sounds “want” and “need” – these are essential to the communication and translation at the birds’ feeding time – but he’s never heard or needed to practise the caretaker’s sounds for “go out” or “stop” or “keep open.”

Out of desperation, taking a choice to communicate with her physically as he cannot explain his needs to her, the mimic bird jumps into the caretaker’s toolbox.

He nearly fills it completely.

Only the trays in the metal lid and the sides of the box are visible around his feathers.

“Get out, you silly bird,” the caretaker laughs as she gives the mimic bird a loving but firm shove in the breast to get him out of the tool box so that she can get to a slender metal tool with a curved and pointed nib.

With the laugh still lingering as a peaceful smile on her lips and in the creases of her furry face, she picks up the broken panel and rests it squarely in front of her.

The mimic bird turns himself round, sorts out a few of his feathers, and then jumps straight back into the toolbox.

“Oh, come on now,” the caretaker laughs, “please get out.”

She shoves him lovingly in the chest again when she says the last two words, a little harder this time, knocking him out and toppling him over onto the platform high up on the outside of The Aviary.

Then she picks up the roll of silver-plate sheeting and begins to layer it onto the panel using the tool in her left hand to fit it around and into the shapes and gaps of the frame.

The mimic bird quickly rolls back to upright and jumps onto the handle of the toolbox, flapping his wings and squawking.

The caretaker looks at him quizzically.

“What is it?” She asks him. “What words are you trying to say?”

The mimic bird continues wildly flapping and loudly squawking on the handle of the toolbox.

“Seriously, come on now,” the caretaker says, “I really think you need to get off and go back inside.”

She firmly pushes him off the handle and turns back to the hole, picking up the fallen panel and resting it in place.

Hearing a slight difference in the sounds the caretaker used when she shoved him off the handle from when she shoved him out of the toolbox, the mimic climbs back into the toolbox.

“Get out,” the caretaker says sharply as she pushes him again then turns quickly back to her work – popping each of the pretty little iron rivets into their holes in the panel ready to fix it to the frame.

The mimic bird quickly jumps onto the handle again.

“Get off.” She barely turns from her task to push him firmly again.

The mimic bird immediately jumps into the toolbox again.

“Get out.” Her eyes widen, she shoves him, her smile tightens, and her voice darts through the air faster than those little finotias.

She turns straight back to fixing the panel.

He jumps on to the handle again.

“Get off.” She shoves again.

He gets into the toolbox again, moving so quickly he doesn’t give her time to do anything more with the panel.

“Get out.”

He repeats these actions until he’s heard the difference between “out” and “off” as much as he needs, and until he can tell that the caretaker’s frustration is about to snap.

Then he pauses on the platform with his head bowed and right eye turned up.

“What ARE you playing at,” the caretaker smiles and rolls her eyes at him, giving him a gentle stroke and squeeze on the check as she does.

He coos and clucks softly and turns to twist and squeeze his way back into the aviary, falling first from the hole, then turning on the wing as he swoops away to watch the caretaker behind him finally fix the panel and shut the hole, and then transport herself, the platform and all her tools away in her flash of rainbow light.

“I could not stop her, the hole is closed,” the mimic bird squawks as he returns, flying through the middle of the still chanting murmuration, “we can’t go out now,” he continues as he swoops to the ground.

The weight of the dual slipstreams of his words and wings pull many of the birds in the murmuration to the ground with him.

But a small group of fancy roloops streams away from the murmuration in the other direction.

Up.

“Make hole again. Make hole again. Make hole again.” The roloops scream at the top of their little lungs. “Make hole again. Make hole again. Make hole again.”

From the ground below, the mimic bird watches the roloops while the rest of the birds come to land around him.

The roloops crash into the replaced panel one by one in a quick fire rally – trying to break and burst through.

They peck and tug at it frantically with their beaks, and grab and pull it with their claws – trying to rip it off or fly away with it.

But nothing works.

The freshly replaced silver-plated panel does not budge.

The fancy roloops return to the group of birds who are all now back on the floor gathered around the mimic bird.

“Hole still closed,” the roloops cry as they land, “All have safety. None have freedom.”

“All need both. All the same,” the crowd respond to the fancy roloops’ call.

A new chant begins.

“All have safety. None have freedom. All need both. All the same.”

“All have safety. None have freedom. All need both. All the same.”

It would be impossible for anyone to ignore the strength of every voice together asking for what they know they need.

Especially when what they need is so obvious now to everybird.

“All have safety. None have freedom. All need both. All the same.”

“All have safety. None have freedom. All need both. All the same.”

“All have safety. None have freedom. All need both. All the same.”

The mimic shuffles his feathers.

The chant quietens but does not stop. They know what they all want and need now. Nothing can change that. And nothing can stop it. Together they are aware and speaking as one.

The mimic bird raises his song over the clear, confident chant of all the birds together as one.

“I heard the noise she uses for open. I will learn to sing it to her, so I can tell her what we need.”

The mimic bird jumps down from the tree stump and walks through the crowd towards the feeding area.

When he arrives, he settles down at the foot of the fossilised light plant before night falls.

At first, he simply begins to shape his throat and tongue, silently practising the patterns he needs to vocalise the new sound.

And soon, he tries noise after noise under his breath.

“Aaaaaaaa d, aaar d, oooaaar d, d…”

“Have you learned yet? I want to go out again,” twitters a tchicket as it zips by.

“…d, d, td, dt, d, td, t, t, t, aut, au, oooo a t, oooo u t, ooo u, oooo wu…”

“I’m going to find the most beautiful view in all of the forest when we can go out again,” coos one of the muse birds from a treetop.

“…oo wu, oowu, owu, owu t…”

“I can’t wait to make friends with wild birds,” clicks one of the birds of wonder as it drinks from the spring.

“A wut, a wut, awut…”

“…owut, owut, owu, owu, ow, ow…” the mimic continues.

“I hope the aviary will always be safe inside.” Two of the day curblers come and stand in front of him to sing this in unison and harmony.

“…ow t, ow t, owt, owt, owt…” he continues, and as he gets more confident the mimic bird vocalises the sounds clearly.

The curblers stand listening to him practice, bopping their heads and bodies, enjoying the new rhythms he is making.

“…owt, owt, owt, j, j g, h, hie, het, get out…” the mimic shuffles his feathers “…nu ee d out, nueed out, need out…” he stands and raises his voice “…la i, lai, ly k out, like out…” he begins strutting as other birds gather around him “…wu on t, wuon t, wuont, wont, want, want, want, want out.”

He pauses and looks around.

All the birds dash through the dusk to gather together around the mimic bird. They settle there for the night in the bushes and trees, with the tiny finotias tucked up in their nests on the ground under the largest of mushrooms.

“Get out, need out, like out, want out,” the mimic speaks triumphantly in his high breathy whistle.

To his satisfaction, and to all the sleepy birds’ joy, he has been able to learn to express feelings and needs clearly in the caretaker’s language with more detail and variety than his usual simple translation and repetition of food names at breakfast.

He feels full of confidence that he will be able to easily communicate their needs to the caretaker, so he too settles to sleep while The Aviary sings softly with hope all night.

The tireless little finotias wake up the earliest and zip straight to the feeding area. The other birds wake almost immediately after them and follow.

The mimic bird is last to wake and arrives at the back of the crowd to find them singing and dancing to a new song together, to a gentle tune that developed over night.

“Safety and freedom for every bird.”

“Safety and freedom for every bird.”

“Safety and freedom for every bird.”

Their song is so loud that the mimic does not hear the caretaker’s song about food as she approaches, and they are dancing so impatiently around him that he doesn’t see her arrival.

The birds do not react either, still singing their new song at the tops of their little lungs and dancing with passion and hope filling their bodies.

The caretaker stands for a few moments laughing and smiling.

“Wow! You are very excited today, aren’t you. Let me just give you everything that I have brought.”

She crouches before them and opens one of the bags of food.

The birds continue dancing and singing together.

She begins to make piles of the different food around them.

The birds continue dancing and singing together.

“Safety and freedom for every bird.”

The caretaker finishes laying out the food in small piles all around, then laughs to herself again as she and looks up at the crowd of still dancing and singing birds.

“Are you lot not hungry today then?”

There is no response, the birds just continue dancing and singing together.

“What is going on?” She laughs nervously this time, looking at the mimic bird who is also singing along with the birds.

The songs and dance continues.

“I’m not sure what’s going on here, but I do need to change out of these dirty clothes.” She looks at the mimic bird. “I wish you could tell me what all this is about. I will be back in a moment to find out.”

She disappears in a rainbow flash and then reappears almost immediately wearing softer clothes with her long hair flowing.

She crouches beside the mimic, strokes his face and head, and looks him inquisitively in the eye.

“Can you show me what this is about, please?” She says.

He looks her calmly in the eye too and opens his beak.

“When the hole was open, many of us enjoyed…” the mimic bird cuts himself off with a short sharp inward breath, while blinking and shaking his head briefly.

The birds’ song of freedom and safety rises to fill the gap in the air and the caretaker looks at him attentively, trying not to make him nervous by showing how full of joy she is that he is now able to speak properly to her or how confused she is that he has suddenly developed this new ability.

“…many enjoyed the freedom we experienced.”

He pauses again, this time to fully feel the contentment and confidence that fills him as he finds his voice when he most needs it.

“We all want to keep the safety of the aviary because we love it here. We love your protection. But we also want to be able to explore the full freedom outside. We didn’t realise until now that our freedoms inside the aviary were smaller than the full possibility of freedom. Please open the hole again so that we can choose when we are protected and when we are free.”

The caretaker smiles.

The caretaker disappears in a flash of rainbow light again and reappears immediately with her tools and her hair in a loose bun.

She starts to undo the bolts on one of the panels at ground level on the edge of the feeding area.

Seeing her opening up the aviary again, the singing birds flock, fly and flit around the piles of food; finding new flavour combinations of different seeds, nuts, berries and grubs. Excitedly taking a far less orderly approach to breakfast than usual.

The caretaker finds the first panel needs be tugged and twisted hard from its fixings to the frame. But once she moves on to the three panels around it – one to the right, and then the two above those – each proves easier to remove than the last.

Many of the birds take small breaks from feeding to fly past and check out her work.

The hole is much larger than the original and, being at ground level, it will let all the birds use it easily – even those who are tired or find it hard to fly high.

Seeing that it is nearly ready, the birds begin to gather around her, eager to use the new hole.

She carefully folds smooth silver plating around the edges; neatening it, making it safe – tucking it in, almost – and leaving it so well finished that it looks like it has always been part of the aviary.

The caretaker moves away from the hole, takes down her hair and begins to pack away her tools. The still singing birds at once begin to zip and zoom in and out. Her heart flies with them. She feels their freedom as hers. She feels it is rooted in the safety she provides.

The mimic bird walks slowly through the hole with his head held high, and then turns back to the caretaker.

“What will you do now that we won’t always all be in the aviary?” His eyes sparkle as he speaks.

“Nothing will change for me. I still love the aviary. I still love you all. And I still love all the beings in the forest and in the universe. I will still take care of the aviary. I will still make sure that inside the frame of the aviary, it is always safe and comfortable for everyone. I will still bring food every morning for anyone in the aviary. The aviary will remain a place of beauty, rest, safety, and abundance for all to share. I will even take care of and protect beings who did not live here before the hole if they want to come in for a rest. I will still always be here, too. Nothing has changed. Except…” she tails off, waiting for her feelings to clarify before she continues.

“Except what?” The mimic bird asks, tilting his head to the left, ruffling his wings and scratching at the yellow dusty ground.

“Now that you can all leave when you want,” she continues, with a peaceful smile filling her face, “I am happier.”

“You are happier without us all here all the time?” The mimic bird asks, lowering his eyes and feeling a little disheartened by her answer.

“Not quite, my darling.”

Realising her intention was not well conveyed, the caretaker crawls out of the hole and gives the mimic bird a cuddle.

“Nothing has changed for me. I have everything I had before, and I do everything I did before. I have lost nothing. But you have gained more freedom. And it is your freedom that makes me happier than before. I didn’t know you weren’t free either. You are all so beautiful, I wanted to protect you. I built the aviary to keep you safe. And I gave you as much freedom as I thought you’d always need. But you have lived for generations in here now. You have built your own wisdom and knowledge. You all have strength within yourselves. And the birds I have brought in through the years to look after, they have helped you develop together too. You have strong families and communities. You have everything you could need. But I didn’t know you weren’t free. Or, more to the point, I thought the freedom I gave you was and would always be enough. I couldn’t see you were constrained by my protection, I didn’t realise that my definition of freedom curtailed you, until you found the voice to tell me so. I couldn’t see my love for you had gone too far or wasn’t going far enough. I am ever so happy that you are free now. And I dearly hope I will still see everyone at least sometimes.”

She smiles, hoping this answers the mimic bird’s concern.

“We would not have become so strong if you had not given us the safety and space to grow within the safety of aviary.”

The mimic bird leans against the caretaker’s leg and looks up at her, his eyes asking for a stroke.

“But we are glad now that we have the choice to be completely free as well as to live inside your beautiful security. Many of the birds don’t want to leave, so you will still have familiar company. And although I do want to look around outside, I will never be far away, and I will always return to help you with breakfast for whoever is here in the mornings.”

He gently moves away from her hand, looks her in the eye, blinks slowly and bows his head respectfully, then walks off into the deep forest outside the aviary – swishing his beautiful tail behind him as he goes.

The caretaker watches him go, then her rainbow light flashes once and she is gone too.

Somehow the aviary has been entirely and irreparably altered, and yet it has not really changed at all.